KEY POINTS

- Determining the phase of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is essential to the clinical assessment of the patient with HBV.

- HBV DNA, HBeAg status and liver function testing are all vital components of this assessment.

- HBV DNA is an important parameter in informing treatment decision. Testing is Medicare rebatable for one test annually for monitoring and up to four tests annually for those on treatment.

- Fibrosis assessment to determine the stage of liver disease is also important (non-invasive tests, imaging with or without biopsy)

- Non-invasive methods of assessing hepatic fibrosis such as transient elastography (FibroScan®) are now available.

- Normal alanine aminotransferase (ALT) ranges have been revised downwards (< 19 U/L for females and < 30 U/L for males), and normal liver function tests (LFTs) do not rule out significant hepatic disease.

- Transmission risks, lifestyle modification, cultural factors and long-term complications associated with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) infection are important components of patient education.

- When people are diagnosed with hepatitis B, testing, assessment and vaccination should be offered to their household and sexual contacts.

- All patients with CHB require regular monitoring for liver damage and disease progression.

Click to open GESA recommendations

GESA Consensus Recommendation 3

GESA Consensus Recommendation 4

GESA Consensus Recommendation 5

Table 6.1 provides a summary of acute hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection.

|

Table 6.1 Acute hepatitis B virus infection |

|

ALT: alanine aminotransferase; anti-HBc: antibodies to core antigen; anti-HBs: antibodies to surface antigen; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; CHB: chronic hepatitis B; HBeAg: hepatitis B envelope antigen; HBsAg: hepatitis B surface antigen; HBV: hepatitis B virus; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; IgM: immunoglobulin; IU: international units |

|

The incidence of acute HBV infection has been decreasing in Western countries for a number of years, due to widespread vaccination and routine blood testing. Acute HBV infection is characterised by the onset of symptoms 1–4 months after exposure. A serum sickness-like syndrome may occur, followed by an illness characterised by anorexia, nausea, jaundice and right upper quadrant pain. Symptoms usually disappear after 1–3 months, but some patients have prolonged fatigue even after liver function tests have normalised. Elevated ALT/AST with values up to 1000–2000 IU/L are characteristic of acute HBV. Prothrombin time is the best guide to prognosis. In the early phase of infection, HBsAg, anti-HBc IgM and HBeAg are all positive. The disappearance of HBsAg is usually followed by the appearance of anti-HBs. However, the appearance of this antibody may be delayed, creating a window period where the diagnosis of recent HBV infection can only be made by the detection of anti-HBc IgM. A small proportion of patients (0.1–0.5%) will develop fulminant hepatic failure, believed to be caused by massive immune-mediated lysis of infected hepatocytes. Such patients may have no evidence of active viral replication at the time of presentation. The management of acute HBV is symptomatic care. Bed rest and nutritional support are central. Anti-nausea medications may be of benefit, and limited doses of paracetamol (< 2 g a day) or codeine may be cautiously administered for abdominal pain or fevers. Since most patients recover, antiviral therapy is not generally recommended. However, case reports and results from a small series of patients suggest some benefits of early therapy. Current recommendations support the use of nucleos(t)ide analogues at the first sign of severe liver injury or impending hepatic failure. Patients should be monitored regularly with laboratory tests during the acute phase of their illness, and referred for specialist review if they have a prolonged prothrombin time, elevated serum bilirubin concentration, and signs of encephalopathy, or if the illness is uncharacteristically lengthy. Continued serological assessment following recovery from the icteric illness is important to identify the small proportion of patients who develop CHB. |

History and physical examination

The assessment of patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) should commence with a thorough clinical history and physical examination. Interpreters are required when patients are not proficient in English. Aspects of the history that deserve close attention are:

- any risk factors for the acquisition of CHB; for example, ethnic background, family history of CHB and family history of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)

- host or viral factors that are associated with an increased risk of cirrhosis; for example, older age (longer duration of infection), heavy alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, and co-infection with other viruses such as hepatitis C virus (HCV), hepatitis D virus (HDV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

The severity of the underlying liver disease should be clinically evaluated by examining for peripheral signs of chronic liver disease, (e.g. spider naevi), portal hypertension (splenomegaly) or decompensation (jaundice, hepatic encephalopathy, ascites and peripheral oedema) (1, 2).

Extrahepatic manifestations of CHB occur in 10–20% of patients, and effective antiviral therapy is pivotal in such patients. An example of such a manifestation is polyarteritis nodosa involving multiple organ systems, including the gastrointestinal tract (colitis), kidney (glomerulonephritis), neurological (neuropathy) and dermatological (vasculitic skin rashes, palpable purpura) systems. Conversely, about 50% of patients with polyarteritis nodosa are positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg). Hepatitis B virus infection-associated glomerulonephritis usually presents with nephrotic range proteinuria, which may progress to renal failure in the absence of effective antiviral therapy (3).

Laboratory investigations

Complete HBV serology – HBsAg, antibody to surface antigen (anti-HBs), antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc), hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), antibody to hepatitis B e antigen (anti-HBe) (Table 6.2) – and measurement of HBV DNA level should be performed initially to evaluate HBV replication status (1). HBsAg is the first serological marker to appear, and its presence for more than 6 months indicates CHB infection. HBsAg appears in serum 4–10 weeks after exposure, preceding the onset of symptoms of acute hepatitis and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) elevation. HBsAg will become undetectable 4–6 months after acute exposure in those patients who achieve successful immune clearance (see: Hepatitis B virus testing and interpreting test results) (1, 2, 4).

Anti-HBs indicates immunity to HBV when the antibody emerges following the disappearance of HBsAg. Anti-HBs usually persists for life, conferring long-term immunity (1, 2, 4).

HBcAg is only expressed in liver tissue and is therefore not used in routine clinical practice. Anti-HBc is a marker of exposure. Anti-HBc immunoglobulin M (IgM) is seen in high titres in acute HBV infection, and at lower levels in patients with CHB undergoing a flare in disease activity.

|

Table 6.2 Tests used in the initial assessment of patients with chronic hepatitis B |

|

|

Test |

Why the result is important |

|

HBeAg / anti-HBe Anti-HAV, anti- HCV, anti-HDV, HIV Ag/Ab |

Quantify replication, identify phase of infection and consider treatment Ascertain co-infection (with HCV, HDV or HIV) and evidence of immunity to HAV (need to offer vaccination) |

|

LFT |

Necroinflammatory activity, synthetic function |

|

anti-HBe: antibodies to envelope antigen; FBC: full blood count; HAV: hepatitis A virus; HBeAg: hepatitis B envelope antigen; HBV: hepatitis B virus; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV: hepatitis C virus; HDV: hepatitis D virus; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; INR: international normalisation ratio; LFT: liver function test; PT: prothrombin time; AFP: alpha fetoprotein |

|

HBeAg is considered a marker of HBV replication and infectivity. Seroconversion (i.e. loss of HBeAg and development of anti-HBe) often signals transition from an active phase (immune clearance) of the disease to an immune control phase (HBeAg negative, anti-HBe positive, low HBV DNA level). Patients can fluctuate between the active (HBeAg positive, anti-HBe negative, high HBV DNA level) and immune control phases of the disease over time. The absence of HBeAg, however, does not necessarily exclude active viral replication, since specific mutations in the HBV genome can prevent HBeAg synthesis – the so-called precore and core promoter mutants. Patients with these HBV mutants have elevated HBV DNA and ALT despite the absence of HBeAg (HBeAg-negative CHB or immune escape). For a discussion of the definition and preferred terminology of CHB see Natural history of hepatitis B virus infection.

HBV DNA level is a measure of viral replication, used as a criterion for commencing antiviral therapy in patients with CHB in conjunction with evidence of ongoing liver damage. In population studies, a HBV DNA level greater than 2000 IU/mL was found to be a strong predictor of increased risk of cirrhosis and HCC (5). Results of HBV DNA levels were previously expressed as copies/mL, but the current standard is to convert them to international units (IU)/mL. The conversion factor ranges from 5.2 to 5.8, depending on the laboratory. Currently, most HBV DNA assays are based on real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which provides increased sensitivity and greater dynamic range quantification than hybridisation assays. An earlier version of the hybridisation assay, used commonly until a few years ago, has a threshold of detection greater than 20,000 IU/mL (> 141,500 copies/mL). Hence, the clinical status for some patients may need to be reinterpreted using the results obtained with the newer assays. In particular, patients with HBeAg-negative CHB (immune escape) might be erroneously diagnosed as inactive

or being in the immune control phase, because of the inability of older assays to demonstrate viraemia below the assay detection threshold.

The threshold of HBV DNA level associated with liver disease is unknown. However, treatment is usually considered in HBeAg-positive patients with HBV DNA levels of at least 20,000 IU/mL, and in HBeAg-negative patients with HBV DNA of at least 2000 IU/mL (1, 2, 4). HBV DNA levels may fluctuate widely in CHB. More accurate assessment of the patient’s clinical status requires serial measurements of HBV DNA.

Laboratory evaluation should also include an assessment of liver enzymes, hepatic synthetic function (including coagulation profile), and liver ultrasound and alpha fetoprotein (AFP) estimation. A complete laboratory screen for other causes of liver dysfunction and testing for co-infection with other viruses (e.g. hepatitis C and D) are also recommended (1, 2, 4).

Click to open GESA recommendation

Liver biopsy

Liver biopsy should only be performed on the recommendation of a specialist clinician and is now uncommonly needed in assessing viral hepatitis. It provides an accurate assessment of the degree of necroinflammatory activity and extent of hepatic fibrosis, and excludes other liver diseases. The two histological features of liver biopsy used in the assessment of HBV are fibrosis (stage of disease) and necroinflammation (grade of disease). Liver fibrosis is usually graded from stages F0 to F4 (F0=no fibrosis; F1=minimal fibrosis; F2=periportal fibrosis; F3=septal fibrosis linking portal tracts or central vein; and F4=cirrhosis with development of nodules and thick fibrous septa). Liver biopsy may be performed percutaneously or – in those with ascites or significant coagulopathy – via the transjugular route. It has been the gold-standard investigation for determining the stage of fibrosis or liver disease. A number of different scoring systems have been developed to stage fibrosis and grade inflammation. Prominent among these are the Scheuer Score, Histological Activity Index (HAI), the Ishak modified HAI and the METAVIR system, which is used mainly for hepatitis C (6-8).

The development of significant fibrosis (stage 2 or greater) implies progressive disease and the need for treatment. Inflammation is graded using necroinflammatory scores.

Liver biopsy has a number of disadvantages. It is an invasive, uncomfortable, costly and time-consuming procedure that carries a small but significant risk of complications. For these reasons, some patients are unwilling to undergo the procedure. Liver biopsy also suffers from sampling bias, because fibrosis and necroinflammation may be heterogeneously distributed in the liver. The absolute requirement for a biopsy before commencing treatment was removed by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC) in November 2011. However, in some patients, biopsy remains the best investigation for determining the true nature of the liver disease, especially in patients with comorbidities associated with liver injury (e.g. obesity, alcohol use disorders and iron storage disorders). The unique value of biopsy needs to be carefully explained to patients and its use only considered when it influences management.

Click to open GESA recommendation

GESA Consensus Recommendation 6

Non-invasive assessment of hepatic fibrosis

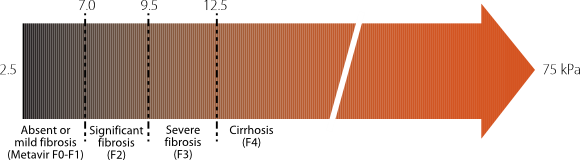

Non-invasive measures of hepatic fibrosis are increasingly available and used. The most commonly used technique is transient elastography (TE) or FibroScan®. It measures liver stiffness via ultrasound elastography. Shear waves are generated and measured in kilopascals (kPa), which correlate with fibrosis score as determined by biopsy. Cut-off value are given that can accurately place the patient in different stages of fibrosis (Figure 6.1).

A meta-analysis of the use of TE in CHB found that it performed well in detecting cirrhosis (sensitivity 85% and specificity 82%), but was less specific at detecting severe fibrosis (sensitivity 74% and specificity 64%). (9). A more recent meta-analysis regarding the use of TE in CHB support these findings, with similar sensitivity and specificity in the detection of cirrhosis (sensitivity 86% and specificity 88%) and better sensitivity and specificity in the detection of significant fibrosis (≥ F2/F3, sensitivity 81-82%, specificity 82-87%) (10). In the detection of cirrhosis in patients with CHB, TE has greater sensitivity and specificity when compared to other non-invasive tests, such as FIB-4 and APRI (11). Australian and international consensus guidelines now include TE as an acceptable alternative to biopsy for fibrosis staging (1,2,12-14). Currently, FibroScan® is available in a wide variety of setting although is not universally available . There is no Medicare rebate for these services, and access is usually offered as part of a specialist review.|

Figure 6.1 Clinical significance of liver stiffness cut-off values in chronic liver diseases using FibroScan® (18) |

|

Used with permission: Castera L, Forns X, Alberti A. Non-invasive evaluation of liver fibrosis using transient elastography. J Hepatol 2008;48:835-47. |

A number of other means of assessing fibrosis non-invasively have been reported. They include acoustic radiation force impulse (ARFI), shear-wave elastography (SWE), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-based elastography and serum blood algorithms, such as those used to derive the aspartate aminotransferase (AST) to platelet ratio index (APRI), Fibrotest and Hepascore results. APRI can be calculated from AST and platelet count and is used to evaluate the presence of cirrhosis in hepatitis C in the current Australian consensus guidelines (15). Predicting cirrhosis in hepatitis B with an APRI score greater than 1.5 has a sensitivity of 54% and specificity of 78%. With a 2.0 cut-off value, the APRI has a sensitivity of 28% and a specificity of 87%. For predicting fibrosis more than F2 and a cut-off 1.5, the sensitivity is 49% and the specificity is 84%. With a 0.5 cut-off value, the sensitivity is 84% and the specificity 41% (16). The APRI score is currently recommended by the WHO for evaluation of cirrhosis in CHB in low- and middle-income countries using a threshold over 2.0 but detects only one-third of patients with cirrhosis (17). Further research into non-invasive assessment of hepatic fibrosis is required.

Click to open GESA recommendation

GESA Consensus Recommendation 5

The need for treatment is based on assessment of HBV DNA and liver function tests (to determine the phase of infection), and assessment of fibrosis. Candidates for treatment are those with HBeAg positive or negative chronic hepatitis (previously known as immune clearance and escape phases respectively), and all patients with cirrhosis. Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) criteria for initiating therapy are given in Table 7.2 (see: Treatment of chronic hepatitis B virus infection). All patients with CHB require some form of monitoring, the frequency of which is determined by their clinical state (Table 6.3).

|

Table 6.3 Monitoring patients with chronic hepatitis B |

|||

|

Indication |

Monitoring specific to phase |

PLUS, monitoring for all phases |

|

|

HBeAg-positive chronic infection (previously referred to as Immune Tolerance) |

|

|

|

|

HBeAg-negative chronic infection (Previously referred to as Immune Control) |

|

||

|

On treatment

HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis (previously referred to as Immune Clearance)

HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis (previously referred to as Immune Escape)

|

3-monthly for the first year, then 6-monthly:

In addition

Also assess adherence to treatment every review |

||

Monitoring for those not on treatment consists of LFTs 6-monthly and HBV DNA annually (Medicare rebatable once every 12 months). The monitoring is needed to determine if and when the disease phase has changed and when treatment may be indicated.

Click to open GESA recommendation

CHB can be a life-long disease, and it is important to counsel patients as carefully as possible about the disease, the risks of transmission, and the role of therapy and its limitations. The epidemiology of CHB indicates that most patients will come from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people also have a high prevalence of CHB, up to four times higher than non-Indigenous Australians (19). It is important to ensure that counselling patients about CHB is done in a culturally appropriate and safe manner. Health practitioners need to be sensitive about the cultural beliefs of specific patient groups, and aware of the implications of a diagnosis of CHB in various patient populations. When there are language barriers, an accredited interpreter is essential to ensure that information is properly understood and that the patient has an opportunity to ask questions. Family members can be of great support to the patient, but should never be used in place of a qualified interpreter. The Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) has a number of services, including the Doctors Priority Line 1300 131 450 (which is freely available, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week). For more information on TIS (National), and links to HBV information packages in other languages, see: Health professional resources.

Various lifestyle issues need to be addressed: alcohol consumption should be at safe levels and avoided (20) in people with fibrosis or cirrhosis , and cigarette smokers or cannabis users should be strongly encouraged to quit. Weight reduction should be encouraged for those who are overweight or obese (based on body mass index), and sound nutritional advice should be provided. Vaccination and transmission issues should be addressed (see: Primary prevention of hepatitis B virus infection).

Click to open GESA recommendation

GESA Consensus Recommendation 20

All patients should understand the aims of treatment (with the assistance of language interpreters where necessary), namely:

- to achieve prolonged suppression of HBV replication

- to arrest (or reverse) the progression of liver damage, with the ultimate goal of preventing cirrhosis, HCC and liver failure.

Patients need to have an understanding of the key factors that influence the decision to commence treatment, including the role of liver biopsy. (Table 6.4) some examples of when to seek urgent advice or referral.

|

Table 6.4 Critical situations and the need for referral |

|

Severe acute exacerbation (or acute HBV)

Reactivation during immunosuppression/chemotherapy

Cirrhosis (especially where suggestion of decompensation) Possible HCC found on surveillance Read more on hepatocellular carcinoma in Chapter 10 |

HBV: hepatitis B virus; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma

|

Identifying a patient with cirrhosis

Remember, patients with advanced disease may have normal liver function test results. ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase |

An important element in the assessment of a patient with CHB is HCC screening; this is recommended for patients with CHB who are at high risk of HCC (Table 6.5). Screening is recommended every 6 months using ultrasound with or without AFP estimation (1, 2, 4, 13, 14, 21).

The incidence of HCC is lower in patients receiving nucleos(t)ide analogues (based mainly on data from treatment with lamivudine or adefovir) or interferon than in untreated patients, even in those without cirrhosis (5, 22). However, screening for HCC needs to continue, regardless of treatment outcome, because the risk is not completely eliminated

|

Table 6.5 Recommended screening for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) screening in |

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

HBsAg = hepatitis B surface antigen; HCC = hepatocellular carcinoma;

† Based on Northern Territory linkage data. (24) ^ Such as confirmed or likely high risk HBV genotype. Genotype testing is not routinely offered and not subsidised through the Medicare Benefits Schedule.

These surveillance guidelines are based on the CCA HCC Clinical Practice Guidelines. Alternative guidelines are offered in the Australian recommendations for the management of hepatocellular carcinoma: a consensus statement.

The assessment of patients with CHB infection is complex because it requires an intimate knowledge of the natural history of the disease. Current understanding of CHB has improved dramatically, and new therapeutic agents have altered the management of patients in recent years (see: Treatment of chronic hepatitis B virus infection). Treatment paradigms of CHB are constantly changing. Primary-care doctors will need to keep abreast of these developments to properly advise their patients of the most appropriate management plan. Imparting current knowledge is particularly relevant because current migration patterns suggest that the prevalence of disease in Australia will continue to increase.

- Terrault N, Bzowej N, Chang K, Hwang JP, Jonas MM, Murad MH; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. AASLD guidelines for treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 2016;63:261-83.

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol 2017;67:370-98.

- Yi Z, Jie YW, Nan Z. The efficacy of anti-viral therapy on hepatitis B virus-associated glomerulonephritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Hepatol. 2011;10:165–73.

- Digestive Health Foundation. Australian and New Zealand Chronic hepatitis B (CHB) recommendations. Summary and algorithm. 2nd edition 2010.

- Sung JJ, Tsoi KK, Wong VW, Li KC, Chan HL. Meta-analysis: treatment of hepatitis B infection reduces risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Alimentary Pharmacol Ther 2008;28:1067–77.

- Ishak K, Baptista A, Bianchi L, Callea F, De Groote J, Gudat F, et al. Histological grading and staging of chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol 1995;22:696–9.

- Bedossa P, Poynard T. An algorithm for the grading of activity in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 1996;24:289–93.

- Poynard T, Bedossa P, Opolon P. Natural history of liver fibrosis progression in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Lancet 1997;349:825–32.

- Chon YE, Choi EH, Song KJ, Park JY, Kim do Y, Han KH, et al. Performance of transient elastography for the staging of liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 2012;7:e44930.

- Li Y, Huang Z, Wang Z, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the diagnostic accuracy of transient elastography for the staging of liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Alimentary Pharmacol Ther 2016;43:458-69.

- Singh S, Muir A, Dieterich D, Falck-Ytter Y. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Technical Review on the role of elastography in chronic liver diseases. Gastroenterology 2017;152:1544–77.

- Kemp W, Levy M, Weltman M, Lubel J; Australian Liver Association (ALA). Australian Liver Association (ALA) expert consensus recommendations for the use of transient elastography in chronic viral hepatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;30:453-62.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Hepatitis B (chronic): diagnosis and management. Clinical guideline. Published 26 June 2013. Available at: nice.org.uk/guidance/cg165 (last accessed 23 June 2018).

- Sarin S, Kumar M, Lau G, Abbas Z, Chan HL, Chen CJ, et al. Asian-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatitis B: a 2015 update. Hepatology Int 2016;10:1-98.

- Hepatitis C Virus Infection Consensus Statement Working Group. Australian recommendations for the management of hepatitis C virus infection: a consensus statement. August 2017. Melbourne: Gastroenterological Society of Australia; 2017.

- Parikh P, Ryan JD, Tsochatzis EA. Fibrosis assessment in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. Ann Transl Med 2017;5:40.

- World Health Organization (WHO).Guidelines on hepatitis B and C testing. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Castera L, Forns X, Alberti A. Non-invasive evaluation of liver fibrosis using transient elastography. J Hepatol 2008;48:835-47.

- Graham S, Guy R, Cowie B, Wand HC, Donovan B, Akre SP, et al. Chronic hepatitis B prevalence among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians since universal vaccination: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis 2013;13:403.

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol. Last updated 20 March 2018. Available at: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/health-topics/alcohol-guidelines(last accessed 26 June 2018).

- Wong GL, Chan HL, Tse YK, Chan HY, Tse CH, Lo AO, et al. On-treatment alpha-fetoprotein is a specific tumor marker for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis B receiving entecavir. Hepatology 2014;59:986–95.

- McMahon BJ. Epidemiology and natural history of hepatitis B. Sem Liver Dis 2005;25:3–8.

- Papatheodoridis G, Dalekos G, Sypsa V, et al. PAGE-B predicts the risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma in Caucasians with chronic hepatitis B on 5-year antiviral therapy. J Hepatol 2016; 64: 800-806

- Parker C, Tong SY, Dempsey K, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in Australia's Northern Territory: high incidence and poor outcome. Med J Aust 2014; 201: 470-474.

- Hepatocellular Carcinoma Consensus Statement Working Group. Australian recommendations for the management of hepatocellular carcinoma: a consensus statement. Melbourne: Gastroenterological Society of Australia, 2020. Available at: https://www.gesa.org.au/resources/hepatocellularcarcinoma-hcc-management-consensus/

David Iser - Department of Gastroenterology, St Vincent’s Hospital; Infectious Diseases Unit, Alfred Hospital, Melbourne VIC

Joe Lawler - Department of Gastroenterology and hepatology, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital. Sydney, NSW

Acknowledgement authors original chapter in 2012

Darrell HG Crawford - School of Medicine, University of Queensland, Greenslopes Private Hospital, and Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Princess Alexandra Hospital, Brisbane QLD

Nghi Phung - Department of Addiction Medicine, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Westmead Hospital, Westmead NSW

Metabolic comorbidities including obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypertension and dyslipidaemia should be screened for and optimally managed in people with chronic hepatitis B.

To see the full list of recommendations, see the Australia consensus recommendations for the management of hepatitis B infection here.

Liver biopsy should only be considered when it influences management (e.g. uncertainty regarding the staging of fibrosis or co-existent pathologies).

To see the full list of recommendations, see the Australia consensus recommendations for the management of hepatitis B infection here.

Non-invasive assessment of liver fibrosis should be performed in all people with chronic hepatitis B as part of initial assessment.

To see the full list of recommendations, see the Australia consensus recommendations for the management of hepatitis B infection here.

Evaluation of people with chronic hepatitis B infection should include repeated assessments (e.g. HBV serology, ALT, HBV DNA level) to determine phase of disease and requirement for antiviral treatment.

To see the full list of recommendations, see the Australia consensus recommendations for the management of hepatitis B infection here.

The upper limit of normal for serum alanine aminotransferase should be considered 19 IU/L in females and 30 IU/L in males.

To see the full list of recommendations, see the Australia consensus recommendations for the management of hepatitis B infection here.